Uniform Type Identifiers

Uniform Type Identifiers — a reintroduction

When you save a picture to disk, it produces what's called a regular file. That's POSIX terminology for a sequence of bytes stored on disk.

The Portable Operating System Interface (POSIX) is a family of standards specified by the IEEE Computer Society for maintaining compatibility between operating systems.

How does the system know that this is an image, in this case saved as JPEG, rather than a text file or an MP3 track? Files are sequences of bytes, so you might expect that the system cracks it open and reads the bits inside to figure it out. Actually, the system almost never does that because it's extremely expensive and requires read permissions most processes don't have.

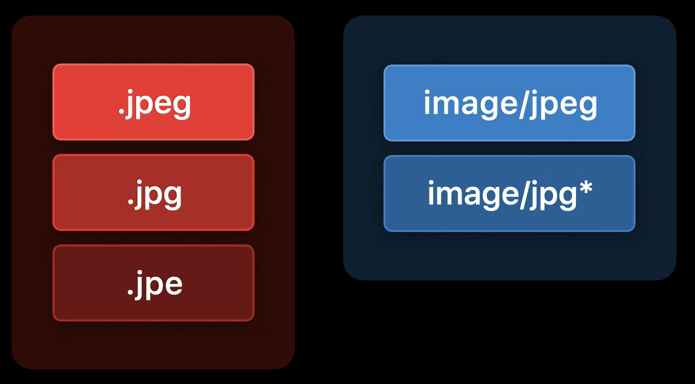

In fact, the operating system bases most of its decisions on the file's path extension. On the web, however, use MIME type. So you see for jpeg image, there are five different pieces of metadata, all representing exactly the same thing.

Well, on Apple's platforms, that's okay, because we use a single string called a uniform type identifier to canonically identify this file format. For JPEG images, public.jpeg refers to all JPEG images, whether they're local or on the web.

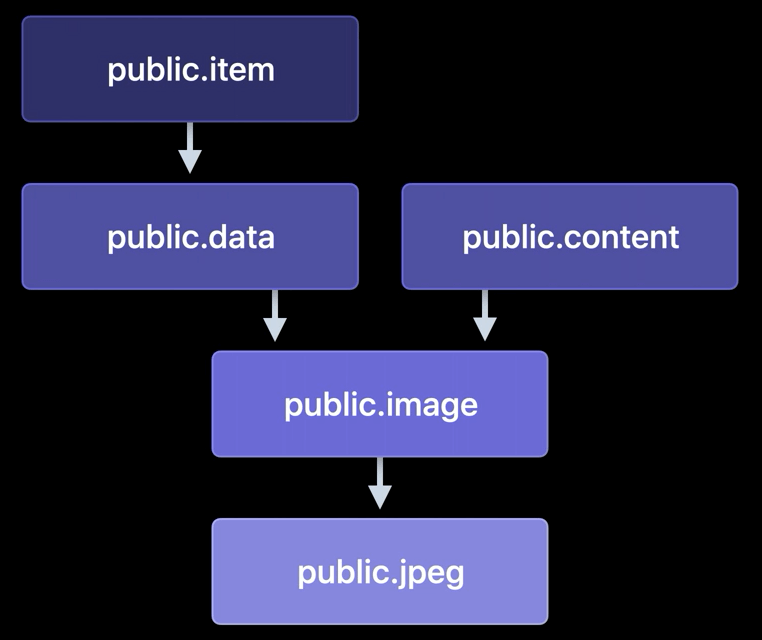

When talking about uniform type identifiers, we say that the public.jpeg type conforms to the more abstract image type. This conformance tree implicitly allows for multiple inheritance (like how protocols work in Swift and Objective-C).

UTI can represent files. But we use them throughout our platforms for other purposes too. For instance, we also use them as the canonical type of pasteboard content.

Many apps create and maintain their own data formats, and these formats deserve their own unique types. If you're using types declared by the system, you don't need to do much. We include a large number of types in /System/Library/CoreServices/CoreTypes.bundle.

When creating your own UTI, there are a few naming rules to follow: UTI are always case-insensitive ASCII and reverse-DNS, such as com.example.file. Ideally, you'll use some more descriptive identifiers. Apple reserves some prefixes or namespaces in identifiers:

public.*is reserved for use by Apple to declare standardized types.dyn.*, fairly rare these days.com.example.*is reserved for templates, examples, sample code and the like.com.apple.*is reserved for use by Apple.

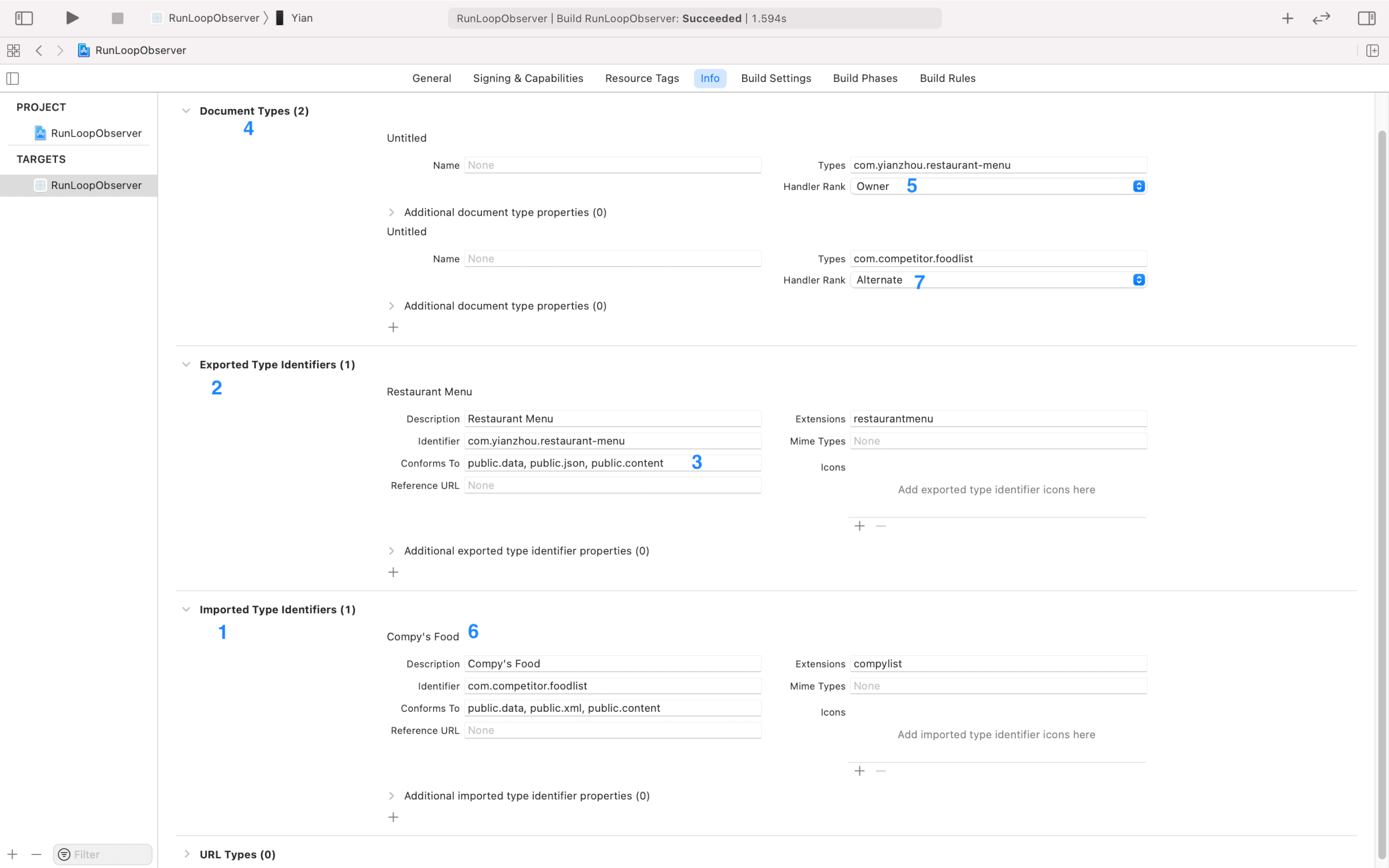

[1] "Imported" tells the system, "This type exists. Here's some information about it."

[2] "Exported" tells the system, "I am authoritative for this type."

[3] Types that represent files in the file system need to conform to public.data if they're regular files-- that is, sequences of bytes-- or to com.apple.package if they're directories that the operating system should treat as files.

[4] Now that we've declared the type, we need to tell the system that our app is able to open it. Expand the Document Type section to add a new supported type.

[5] We should also set this entry's handler rank to Owner. It helps the system intelligently pick the right app for a given job.

[6] Our app has a competitor on the App Store, Compy's Food. Lots of restaurant owners use that app and have saved their menus in the file format owned by that app. We want to also support reading those files. This type was invented by somebody else, and we're only borrowing it, so we need to import it instead of export it.

[7] We're not the owner of the type. Instead, we want our handler rank to be Alternate.

查看 UTI:mdls -name kMDItemContentType -name kMDItemContentTypeTree -name kMDItemKind 1.txt